The following excerpt is taken from Abraham Rechtman’s Yidishe etnografye un folklor (1958) – a memoir documenting his experiences as a researcher with the 1913-1914 ethnographic expedition led by S. An-sky. The expedition visited and documented the lives and customs of around 60 Jewish communities in the Volhynia and Podolia regions of the Russian Pale of Settlement – now part of modern Ukraine.

This is my translation, but the entire memoir has been translated into English by Nathaniel Deutsch and Noah Barrera in ‘The Lost World of Russia’s Jews: Ethnography and Folklore in the Pale of Settlement’, which also contains a fascinating introduction by Deutsch. It is well worth reading in full.

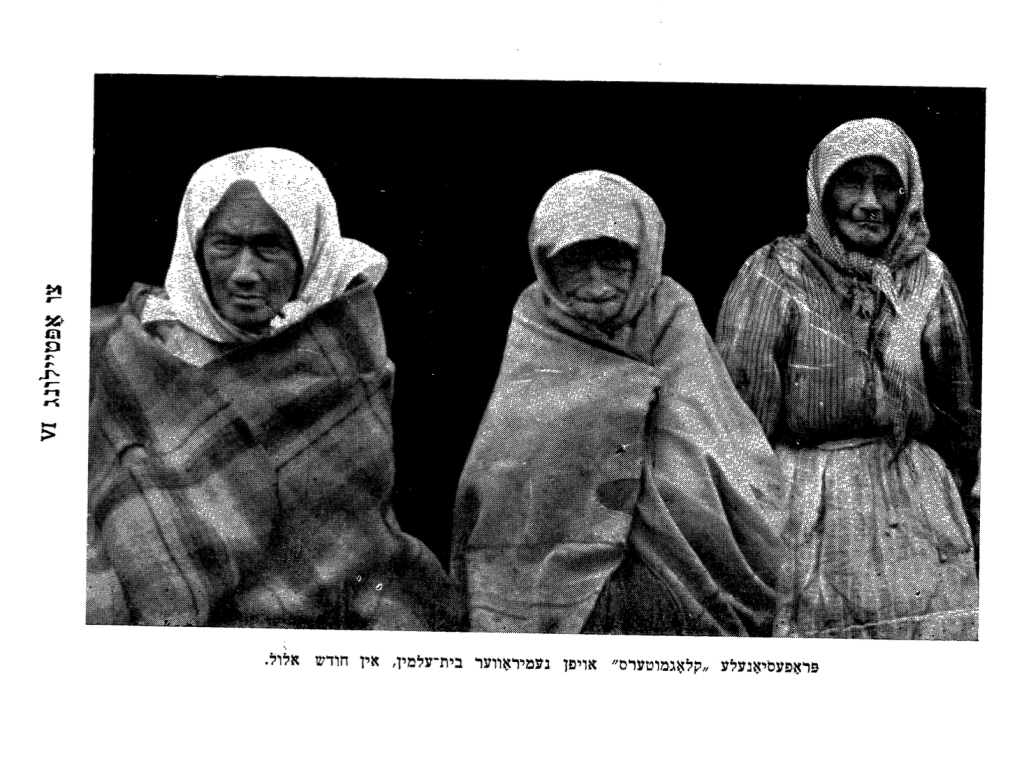

Klogerins and Baveynerins – lamenting and wailing women

Apart from the usual type of opshprekherkes (female exorcists and healers), who could be found in every city and town, we also encountered, albeit in very small numbers, the remnants of a rare type of female elder – klogmuters, whose work, whose calling was to weep and lament and also to bring others to tears.

If someone died, God help us, they came to cry and lament over them. If someone became dangerously ill or was dying, they did everything they could, wailing over the holy ark and over graves to try to save them. They did all of this with professional knowledge.

They would burst in in a place of worship with a clamour, with a heart-rending cry. Throwing open the doors of the holy ark, they flung their heads inside and kissed the Torah Scrolls, losing themselves in a bitter lament, screaming at the top of their voices and begging that the sick person should recover quickly. In a custom known as raysn kvorim (lit. tearing or wailing over graves),they went wailing to the “holy place” – the cemetery. There, they spread themselves out over the graves of the sick person’s relatives, praying fervently to awaken the dead so that they would rise from their graves to go knock on the gates of mercy and entreat on the sufferer’s behalf.

On the wedding day of an orphaned bride, the klogerins took her to her parents’ graves. They wished the parents Mazel Tov and invited them to their child’s wedding. They shed streams of tears over the fact that they, the loyal parents, would not have the honour of leading their good, dear child to the wedding canopy. They listed the virtues of the groom, and asked the parents to intercede on behalf of the bride and her beloved.

In the month of Elul, they spent entire days in the cemetery. People coming to visit their relatives’ graves would hire them to mourn over their loved ones. The klogerins merely asked the name and the mother’s name of the deceased, and suddenly, abruptly, with no special preparations they would break out in a heartrending lament, hitting themselves on the head, beating their hearts and improvising unique prayers and petitions. Like this they went from grave to grave, spilling out tears, lamenting and wailing, extoling the virtues of the dead and begging for mercy for the living.

The klogerins never used any printed tkhines or prayer books. All of their recitations they made up on the spot, so to speak – impromptu. One woman started, and the others repeated after her. Sometimes they would spin out their words, at others they were brief. This usually depended on the payment they received or expected to receive. For a pretty penny, they would really let themselves go – they wept more, sung more praises, raised their voices higher and drew out their laments for longer. For a smaller fee they dallied less.

It was not uncommon to find that, when they had been paid very well, they would go the extra mile: start crying again, throw themselves onto the gravestone and once again list the patron’s virtues.

You will find here a picture of three such old women, ‘professional klogerins’, who we met in the Nemirov (Nemyriv) cemetery during the month of Elul. We spent the whole day shadowing them and writing down their improvised lamentations and liturgical poems. At the end of the day, we rewarded them with a fine sum and wrote down a number of different versions of their chants for usual and unusual occasions, which they recited.

The material is sure to be a great contribution to the treasure of folklore and ethnography gathered by the expedition.

The original photo is held by the YIVO archives. You can also hear me talk about it and about other women spiritual leaders in Yiddish in this interview that I recently did for Swedish TV with my friend Tomas Woodski.

Cite this:

Rechtman, Abraham, Yidishe etnografye un folklor (1958) 306-307. Trans. Annabel Gottfried Cohen.

Leave a comment