This is an excerpt from a short story, “etlekhe yor tsurik” – “Several years ago”, published by an anonymous author in the Yiddish newspaper Kol Mevaser in 1868. The story takes place in a “typical” shtetl in the Pale of Settlement, during one of the dreaded periods of military conscription, when Jewish communities were forced to provide a quota of young men and boys to serve in the Tsarist army. The story’s protagonist is Itse the khaper – child snatcher – who finds a new source of income, working for the kahal or communal board to force the most impoverished boys into service, so that wealthier, privileged families might be spared from losing their sons. However, khaperay (child snatching) is seasonal work. During the rest of the year, Itse, like many Jewish men, is supported by his wife, Itsikhe. In the following short excerpt, we are provided with a list of Itsikhe’s many professions, which includes all of the women’s roles documented on this site.

His wife Itsyekhe is also rather notorious in the shtetl as the holder of several highly prized professions. Were it not for her no-good husband – who, when times are hard, that is to say, when God does not bless them with a period of conscription and the bartender is no longer willing to bribe him with free booze, grabs whatever money there is in the house as soon as it’s earned – were it not for him, she could have been a wealthy woman.

זי איז געװען אַ רופֿאטע, אַ סערװערין, אַ שפּרעכערין, אַ שמשׂטע, אַ זאָגערין, אַ באָבע, אַ קנײטלעך־לײגערין, אַ פֿעלדמעסטערין, אַ טוקערין, אַ סעדיכע, אַ בעקערין, אַ מכשפֿה, אַן אָפּטוערין, אַ קלאָגמוטער, און צו דעם אלעמען איז זי געװען א פּראָצענטניטשקע.

Zi iz geven a royfete, a serverin, a shprekherin, a shameste, a zogerin, a bobe, a kneytlekh-leygerin, a feldmesterin, a tukerin, a sedikhe, a bekerin, a makhsheyfe, an optuerin, a klogmuter, un tsu dem alemen iz zi geven a protsentnitshke.

She was a healer, a servant, an exorcist, a synagogue attendant, a prayer leader, a midwife, a soul candle maker, a cemetery measurer, a ritual bath attendant, a fruit seller, a baker, a witch, a spell-caster, a mourning woman, and on top of all this she was also a money lender. This last career, however, she only pursued during periods of recruitment.

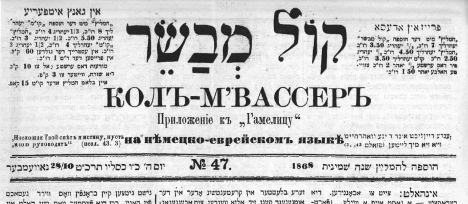

Anonymous, “etlekhe yor tsurik” (several years ago), Kol Mevaser, 47. Odessa, 1868. Trans. Annabel Gottfried Cohen.

Confirming that all of these ritual and spiritual leadership roles were, at least in some places, paid professions, this short excerpt also tells us something about the women who usually held them. While Itse and Itsikhe are both described as notorious, corrupt figures, they are also far from low status, with Itse working directly for the kahal or communal leadership board. Indeed, it is their connection to the shtetl elite that makes them so worthy of criticism.

Condemning the corruption of Jewish communal leaders and the horrific practice of child-snatching – which was sometimes justified religiously, as a way of saving the religious elite, the future rabbis and scholars from recruitment – the author highlights the hypocrisy of a system that claims to act in accordance with Jewish law and ethics. The story is thus also a critique of traditional Jewish religious life, which was portrayed by this and other maskilic writers as backwards, superstitious and removed from what they saw as true Jewish values.

For the purposes of this research, it is significant that he chose to include these women’s religious roles, suggesting they were both important and popular enough to be worthy of criticism. Indeed, the fact that he includes titles like makhsheyfe (witch) and optuerin (trickster) alongside respected women’s roles like bobe (midwife), tukerin (mikve attendant) and zogerin (prayer leader) evidences his desire to portray these female religious leaders as peddlers of superstition. He was not alone. Over the next few weeks, I will publish a few other sources written by male nineteenth century reformers that, presenting these women’s roles in similar terms and portraying them as the female counterparts to corrupt male religious functionaries, also reveal the important place they held in traditional Ashknazi Jewish life.

A note on the source : I came across this story in a class taught by Tal Hever Chybowski at the Paris Yiddish Center. I have recently discovered that this same excerpt was published in a 1959 volume of Yidishe Shprakh, in a short article by Berl Rayman as part of a discussion of ‘women’s occupations.’ You can download the volume here.

Cite this: Annabel Gottfried Cohen, “Itsikhe, the child snatcher’s wife – a list of women’s professions from Kol Mevaser”

Leave a comment