‘Is it customary everywhere to treat the midwife with respect?’

‘Is there a custom that when the midwife dies, all of the children whom she brought into the world accompany her funeral procession with candles in their hands?’The Jewish Ethnographic Program, in Deutsch, the Jewish Dark Continent (2011)

Sources from nineteenth and twentieth century Eastern Europe show that, as in ancient times, the role of the midwife was “understood to be spiritual as well as physical” (Hammer, 2015). Like some of the other women documented on this site, midwives tended to the divide between the living and the spirit world, helping unborn souls to cross over. This spiritual function perhaps helps to explain why, even as modern medicine became increasingly available, many people continued to favour the care of a traditional midwife – known in yiddish as a bobe, heyvn, or heybam – to that of a medically-trained akusherke. In Koriv (Kurów), Poland, the heyvn’s presence at a birth was considered so important that, even when she was in her late 90s and could no longer walk, someone would carry her to the birthing bed on their shoulders.

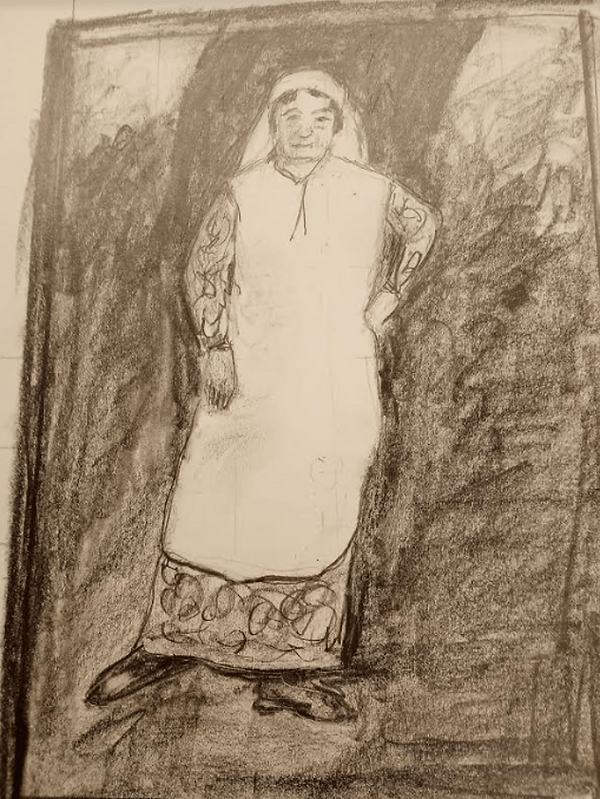

With the process of birth believed by some to create a soul-connection between the midwife and those she helped bring into the world, midwives were often treated as honored elders by the families of the children they helped to birth. In small towns served by only one midwife, this made her a particularly important figure. Following a birth, a midwife would often be given gifts at the bris or naming ceremony of the infant, as well as at other important milestones in the lives of ‘her children.’ One particularly common gift was a white shirt, given to the midwife at the marriage of a child she had birthed. In her famous memoir, Pauline Wengeroff recalled her midwife grandmother-in-law’s ‘great store’ of these white shirts. Like the other women documented here, shtetl midwives tended to be older women – indeed, one common Yiddish word for midwife, bobe, is the same as that for grandmother, hinting both at their elder status and the familial relationship they retained with those they helped to birth.

In some places, it was believed that midwife’s soul remained connected to those of ‘her’ children even after their deaths. In Saratov Province, it was recorded that “when a midwife dies, the women whom she delivered wind ribbons about her hands, so that the dead children may recognize and serve her.” [Listova, 1992] In Wselub, Belorus, a midwife known as Bobe Tzinke hoped to be buried with a girdle in which she had tied a knot for every child she helped to birth – a reflection of the belief that a midwife’s work would be rewarded in the afterlife. Tragically, Bobe Tzinke was murdered by the Nazis, and did not get her wish.

Midwives also served their communities as healers, and were usually well-versed in the kinds of “folk” remedies like pouring wax and led. Most sources suggest that midwives tended to be highly educated in religious as well as medical matters, and particularly religious, going to synagogue regularly – something which was unusual for women. In Khlevisk, near Szydłów, Poland, a healer and midwife named Gitl also acted as a women’s prayer leader. Others acted as community gabetes, collecting money for charitable causes and advising other women on religious issues. Their stories, like those of the other women studied here, suggest that the line between ‘folk’ customs and the Jewish ‘Big Tradition’ was not nearly as sharp as it is often portrayed to be.