In cases of severe illness or very difficult childbirth, Jewish women in Eastern Europe turned to a ritual known in Yiddish as feldmestn or keyver-mestn – cemetery or grave measuring. Often a last resort when other remedies had failed, the graves of close relatives of the suffering person were measured with thread, accompanied by Yiddish tkhines (suppliations) calling on the dead to use their position in heaven to plead with God on behalf of their relative. The thread was then used as the wick for special neshome likht or ‘soul candles’ that were donated to the synagogue or the beys-midresh (the house of study). It was hoped that this mitsve of donating candles to light up the study of torah would invoke God’s mercy.

In times of severe crisis such as plague or if a child was gravely ill, the entire perimeter of the cemetery was measured. The tkhines (Yiddish prayers) and songs said during cemetery measurements, which resemble incantations, compared the thread to the soul or lifeline of the person or people in danger. The act of pulling the thread around the cemetery was hoped to extend the sufferers’ lives. At the same time, it also created a boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead. The tkhines said during soul candle making – a ritual known in Yiddish as kneytlekh leygn (placing wicks) – called on the dead to aid the living and help reinforce that boundary. The very thin, handmade thread, over which was said a special incantation, was known as known as the toyter fodem – the dead thread. It features in a few Yiddish idioms – testimony to the prevalence of the practice, which is frequently mentioned in Yiddish literature describing life in the shtetl.

In many places, cemetery measuring was undertaken by professional women ritualists known as feldmesterins. Like the other women documented on this site, feldmesterins were usually pious female elders who also acted as gabetes – women’s religious experts – and collecters of charity. While in some places feldmesterins were paid for their work, others – like Gitele the Gabete of Koriv and Bobtshe Kilikovski Cohen of Volovisk – performed the ritual behalf of their communities as a mitzvah. Mendele Moykher Sforim, the ‘grandfather’ of modern Yiddish and Hebrew literature, described his mother Sore making soul candles. All of these women were well-educated in religious subjects and also acted as prayer leaders in the synagogue. Gitele di Gabete was even described as the “women’s rebe” of Koriv.

Soul Candles for Yom Kippur

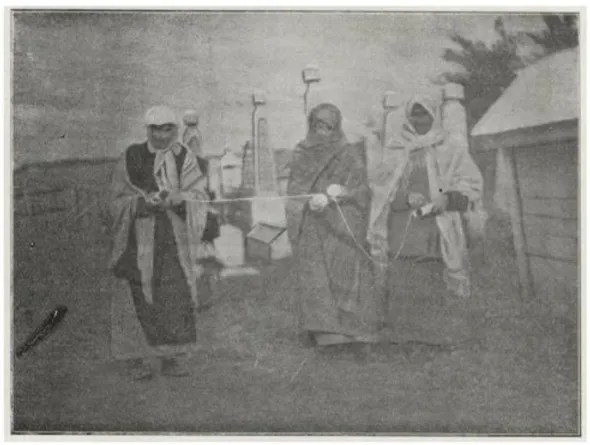

A ritual for times of crisis, in many places cemetery measuring was practiced yearly in the month of Elul, the period leading up to the Jewish High Holidays and the Day of Judgement. While the ritual had become rare by the early 20th Century, a 1906 study by anthropologist S. Weissenberg records that in certain shtetls, feldmesterins could still be found waiting in the cemetery with thread during the week before Rosh Hashanah, when people – mostly other women – would hire them to conduct their measurements. Working in groups of two or three, feldmesterins would generally conduct two measurements of the cemetery perimeter, while their client followed behind them reciting tkhines.

During the eight days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the thread taken from these measurements was used to make huge soul candles or neshome likht. A communal ritual, this was usually led by a female head of household, a zogerin (prayer leader), gabete (religious functionary) or a professional kneytlekh-leygerin (wick-layer) or likhtmakherin (candle-maker). In some places, at least by the 19th century, soul candle making was practiced independently of cemetery measuring, which was becoming increasingly rare, performed only by “particularly religious women.” Soul candle making, however, remained popular, described in several memoirs, including those of Mendele Moykher Sforim, Y. Y. Trunk and Bella Chagall. It was also practiced in some of the great Hasidic Courts, where it was led by the rebetsn in the presence of both men and women.

Printed tkhines for making soul candles listed the merits of biblical ancestors, asking God to have mercy on the living as their descendants. In the most popular printed tkhine for making Yom Kippur candles, authored by the legendary Sore Bas Toyvim, one ancestor in particular – Sarah the matriarch –is called on to advocate for the living in the divine realm (Weissler 1987). Memoirs and ethnographic studies show that most women wrote their own, spontaneous tkhines for soul candle making, calling on their own deceased family members to help them on Yom Kippur. Some women would also name their living relatives and friends, asking for mercy ont heir behalf and offering them blessings for the new year. In some places, it was customary to make two separate candles – one for the living – the gezunte (healthy) or lebedike (living) likht – and one for the dead – the neshome likht. In some places the wick for the “living” candle was taken either from a second cemetery measurement, others from a thread used to measure all living members of the family. On the eve of Yom Kippur, the candle for the living was lit in the home, and the soul candle in the shul.

According to Chava Weissler, the earliest reference to the ritual of making Yom Kippur soul candles is found in a 1197 poem by Eliazar of Worms. Eight centuries later, it remained a popular practice, with prayers for making Yom Kippur soul candles appearing in some of the most popular collections of tkhines. In Sore Bas Toyvim’s hugely popular books of tkhines, the practice of making soul candles is presented as part of the women’s mitzvah of kindling sabbath and festival lights. Seen by Jewish modernizers like Y. Y. Trunk as a superstitious and witchy practice, these tkhines suggest that, for the women who practiced it, it was simply regarded as part of a Jewish women’s tradition that complimented that of men. There is even evidence that the tradition of lighting memorial candles on Yom Kippur – still known in Hebrew as ‘soul candles’ (נר נשמה)– developed out of this women’s practice.

Below you will find my translations of various sources relating to these customs, as well as occasional reflections on reviving and teaching them, and announcements for courses and talks. For anyone interested in trying out these practices, here are some ritual guides I wrote for Ritualwell:

Guide to cemetery and grave measuring as practices to connect with the dead all year round, especially in times of crisis: https://ritualwell.org/blog/cemetery-grave-measuring-and-soul-candle-making-a-ritual-guide/

Guide to cemetery measuring and soul candle making for Yom Kippur: https://ritualwell.org/blog/yom-kippur-cemetery-grave-measuring-and-soul-candle-making-a-ritual-guide/

You can also download the guides in PDF form here